Cybersecurity

Part 2: Skimmers, Shimmers, and You

In Part 1, I pulled back the curtain on my research into modern card skimmers. In this round, we’re hunting for the quiet tells: the subtle indicators of compromise that let you spot a rigged reader before it drains your account.

We’ll dissect the anatomy of a full skimmer attack, then walk through how shimmers and NFC skimmer operations twist the same core principles in this ongoing series on payment fraud.

How To Spot Skimmers

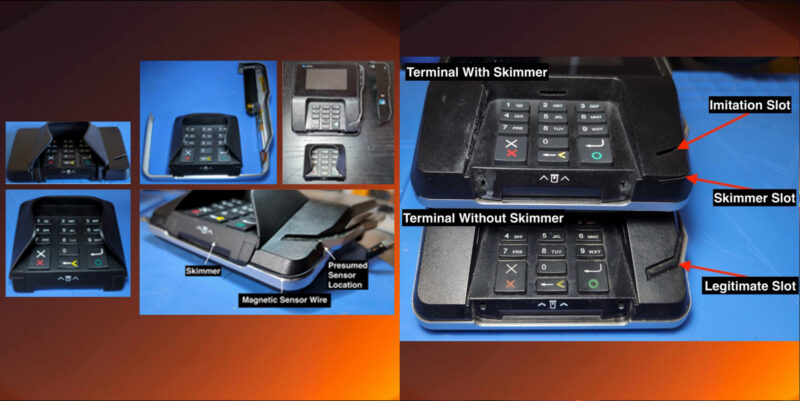

Throughout the analysis of more than 100 point-of-sale skimmers, the same overlay variants kept showing up. The images below show some of the most commonly used overlays for Verifone MX915 terminals. Knowing what these skimmer overlays look like is your first clue in spotting them. When the device is overlaid on top of the terminal, it creates protrusions around the screen and along the terminal’s edges.

The added skimmer PIN pad raises the keypad, with buttons that often look different from the actual terminal’s keys and are harder to fully depress. Most notably, the most common Verifone skimmer overlay adds an extra slot that the victim swipes their card through. That slot contains the skimmer’s magnetic read head, which captures swiped card data and gives the device a clear, distinct indicator of compromise.

Skimmer Detection Tools

As for the industry, retailers and law enforcement have a variety of tools at their disposal to locate skimmers. The most common is the Target EasySweep - this 3D-printed clamshell fits within numerous different point-of-sale terminals to check the tolerance between the chip slot and keypad. Because point-of-sale skimmers overlay an additional PIN pad, the EasySweep won't fit with a skimmer installed, making the device easy to use with little to no training. The device has the unique benefit of remaining affordable at scale, due to Target providing the CAD file to retailers for free.

Alternative identification tools and techniques look for indicators of compromise, such as the skimmer's Bluetooth data or the presence of an additional magnetic read head. As mentioned previously, not all skimmers constantly broadcast over Bluetooth, making wireless detection potentially unreliable. However, provided the detection tool knows what to look for, it can make quick work of noisy Bluetooth skimmers. The most popular example of such a device is the BlueSleuth Pro, commonly used by law enforcement. Some mobile apps claim to contain similar functionality for detecting skimmers wirelessly using a mobile phone's built-in Bluetooth.

Detecting the skimmer's magnetic read head is another reliable option for tools to pursue. Specialized tools such as the Hunter Cat, Skim Scan, or SkimBuster leverage this concept by checking the number of magnetic read heads in a terminal's swipe path. By swiping these devices like you would a card, they detect the inductance of read heads and alert if they locate more than one, indicating a skimmer is present.

Proactively detecting and responding to skimmer incidents, whether from merchants or law enforcement, helps limit victim exposure, reduce brand risk, and keep taxpayers' dollars out of criminals' pockets. Although data breach disclosure requirements vary by state, reporting unauthorized exposure of personally identifiable information (PII) often extends to skimmers and the data they capture. Texas is leading the charge by requiring merchants and financial institutions to report discovered skimmers to law enforcement immediately.

Anatomy of a Skimmer Attack

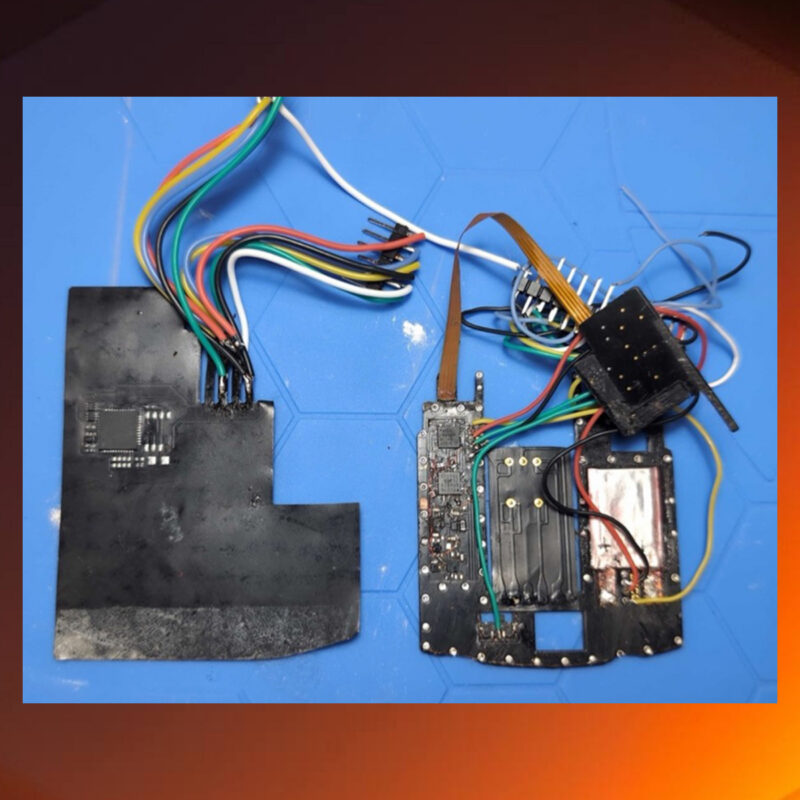

Before criminals can even begin organizing their attack, they must source the skimmer components. This process often entails ordering parts from overseas, primarily from China, via online stores such as eBay, Alibaba, or clear-net criminal marketplaces. A select group of fugitives overseas specifically designs the circuit boards, while different criminals assemble the complete skimmers onshore. For example, take a point-of-sale overlay skimmer: The circuit board ships into the US before being integrated with other components, such as a PIN pad, magnetic reader, and battery. Criminals will then choose the specific terminal to imitate, often by 3D printing an overlay for the targeted device. After they assemble the device, often with copious amounts of hot glue, they either install the skimmer within their own ring or resell the skimmer to other groups.

With devices in hand, fraudsters scope out locations that use a specific terminal model with little to no surveillance. After installing the skimmer in only a few seconds, they will periodically return to retrieve the data from the device. For Bluetooth skimmers, this can mean simply being within a few dozen feet of the device while it's broadcasting. With ATM deep-insert skimmers, however, criminals need to retrieve the device to extract the stolen cards and recharge its battery via a miniature serial connector.

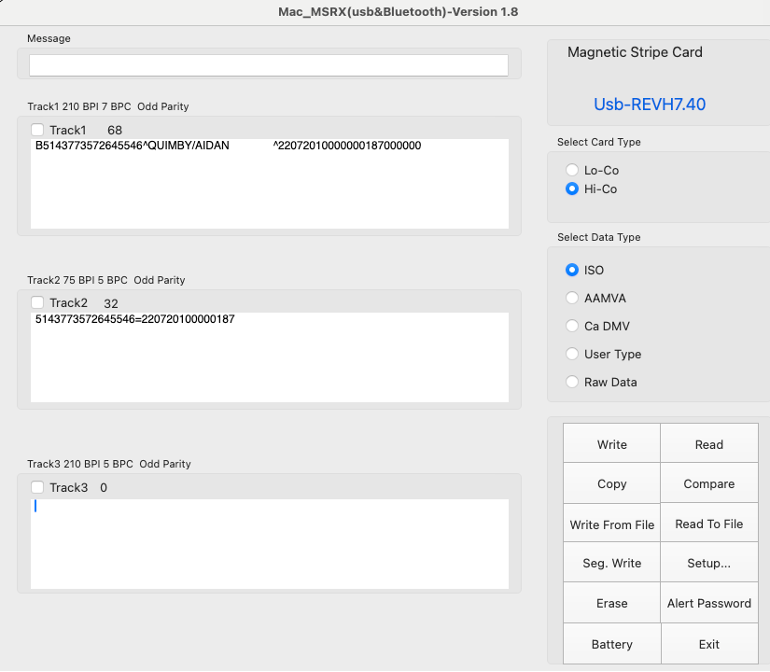

After downloading the skimmed information, modern skimmers require perpetrators to decrypt the data using the same symmetric key programmed into the skimmer's firmware. Once decrypted, the data consists of the magnetic stripe's track two information and the victim's PIN. This track two data holds the card's primary account number (PAN), expiration date, and magnetic stripe card verification value (CVV). Depending on the skimmer's configuration, some criminals also capture the magnetic stripe's track 1 data, which contains the victim's name.

Once the criminals have the data, cloning a magnetic-stripe card can be almost as quick as installing the skimmer. They encode the stolen track two data onto a blank card using a magnetic-stripe writer, and if they want it to look legitimate, they emboss it to match a real card. With cloned cards in hand, they can withdraw cash at ATMs, buy diesel at pumps, or purchase merchandise in stores. In many cases, crews resell large quantities of diesel to gas stations or refueling centers looking to avoid paying federal fuel tax.

Shimmers - The Next Fraud Frontier?

Card shimmers are the equivalent of skimmers for chip-enabled cards. Shimmers achieve this by sitting between the card reader and the inserted card's chip, enabling direct communication with the card during a legitimate transaction. Instead of stealing payment information from the magnetic stripe, shimmers instead target the chip to retrieve what's called "track two equivalent data." Without this data stored within the chip, criminals would have a much harder time extracting cloneable information from the chip's crypto processor.

Chip payments give criminals far more opportunities to capture card data than old swipe-only setups. However, card verification values (CVVs) complicate the picture. These three or four-digit codes exist in three places:

- on the magnetic stripe (CVV1)

- in the chip's magnetic-stripe equivalent data

- physically written on the back of the card (CVV2)

Ideally, each of these values is unique, but some cards have the same CVV on both the chip and the magnetic stripe. Alternatively, some payment processors fail to validate a swiped card's CVV, meaning that even if the chip's magnetic stripe equivalent contains a different CVV, swipe transactions can still be performed with data captured from shimmers. While shimmers are not common in the United States, fraudsters can and will shift to these more lucrative devices when traditional magnetic-stripe skimmers stop paying off.

Shimming and NFC Skimming Demonstrated

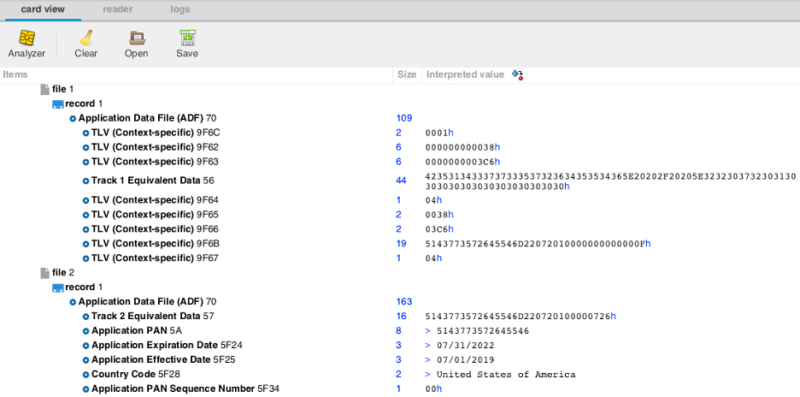

Let’s do a quick demo reading the chip’s magnetic-stripe equivalent data to show the core idea behind shimmers. Using an HID OMNIKEY contact or contactless reader, I can interface a smart card to my computer. Alternatively, most modern smartphones can communicate with payment cards via the right app, since contactless cards use NFC.

For this exercise, I'll use the Cardpeek software to communicate through my smart card reader. Cardpeek sends commands to the embedded microcontroller within the card's chip to enumerate all possible files and their records on the smart card. Once scanned, multiple instances of magnetic stripe equivalent data appear. This data includes the name, primary account number (PAN), expiration date, and CVV, all accessible without entering the card's PIN.

By swiping the same card through a magnetic stripe reader, the data returned is almost identical, except for the three-digit CVV at the end. Criminals can still clone this data onto a magnetic stripe card and perform swipe purchases, but payment processors should detect that the CVV doesn't match the expected value and block the transaction.

Without the ability to produce consistently valid magnetic stripe cards from shimmers, you might be asking, "What's the point?" Well, the only value preventing scammers from using this card data in an online transaction is the CVV2, which is the number usually printed on the back of the card. This three or four-digit value is what most consumers know as their card's CVV, which they're required to enter when making online purchases.

Let that sink in - a three-digit number prevents criminals from making card-not-present (CNP) transactions possible from skimmer and shimmer dumps. Clearly, that's not enough of a deterrent to prevent them from trying, which is why scripts exist to spray a card dump across multiple payment processors to brute-force the card's CVV2.

This attack, known as distributed guessing, was most notably observed in 2017, when researchers published a paper describing the attack vector. At the time, Visa did not block attempts to guess the details from the same card across multiple websites. On the contrary, MasterCard allowed a total of 10 incorrect attempts across all sites before blocking a card. But 10 attempts per card means a criminal could turn a dump of 1,000 magnetic stripes into more than 10 valid card-not-present dumps, as there are only 1,000 potential three-digit CVV2s.

New methods of performing security checks, such as those found in the 3-D Secure payment technology, limit the effectiveness of distributed guessing by centralizing card validation and including up to 150 data fields for verification. The EU mandated the use of 3-D Secure in the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) from 2015, while countries like the United States lack such regulations. Many sites still don't implement 3-D Secure-like technologies, let alone validate your address, which is why card-not-present fraud is continually rising, as shown in a FICO blog from last month.

Your Card is (In)Secure

The most straightforward advice is brief: don't swipe your card.

Beyond that, the attacks presented by shimmers mean "dipping" your chip card isn't entirely secure, either. Similarly, because contactless cards leverage the chip, the same magnetic stripe equivalent data can be retrieved wirelessly. As a result, your card can't be trusted with 100% certainty. Even though modern chip-enabled payment cards provide one-time tokenized values for secure transactions, an attacker can still interrogate your card to retrieve the insecure, hard-coded data.

In contrast, digital wallets like Apple Pay and Google Wallet increase security by always providing one-time payment values, without disclosing a card's plaintext data. It's worth noting that these competing services operate on different principles:

Apple Pay stores card data in your phone's hardware security module, whereas Google Wallet stores a copy in its cloud servers, shifting the attack surface from your phone into the cloud. The numerous expanded protections offered by credit cards over debit cards also provide an additional layer of security, as credit card companies often offer zero-fraud liability.

In the next installment of this series, I’ll walk through the hardware-hacking techniques I use to forensically analyze both skimmers and shimmers.